Also published in Alternet.

Also published in Alternet.

The proposed remarriage of two agrochemical giants with dark histories promises more bad things.

Fifty years ago, the Monsanto and Bayer corporations were forced to separate in order to avoid violating basic antitrust regulations. U.S. courts declared that the two chemical giants, when operating together under the name Mobay, stymied market competition and comprised a monopoly that could not stand.

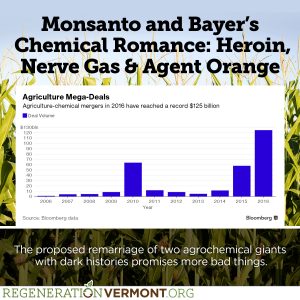

But that was then. Today, under a much different regulatory climate that all but rubberstamps such corporate monopolies, the Germany-based Bayer’s $66 billion offer to purchase Monsanto is being fast-tracked by U.S. regulators. The proposed mega-merger, or re-marriage, will result in nearly 30 percent of all worldwide pesticide and seed sales being controlled by the new partnership.

The merger faces federal antitrust scrutiny before it can be finalized, a process currently underway. It already passed its first test in January when it got the blessings of President-elect Donald Trump, who held an exclusive meeting with the CEOs of both corporations and emerged—not surprisingly—with his thumbs up. Trump’s exclusive meeting with these corporate titans came well before he had even bothered to name his selection to lead the U.S. Department of Agriculture, a not-so-subtle acknowledgement of where the true power lies when it comes to the politics of food.

In addition to market control, Bayer’s proposed purchase is aimed at steadying a reeling Monsanto, which is mired in turmoil from a long list of objectionable activities involving toxic pesticides and its increasingly unpopular genetically-modified organisms. Ironically, given its own sullied past that includes Nazi sympathizing and marketing heroin-laced cough syrup for children, Bayer is being portrayed as the one riding to the rescue of Monsanto’s poor public image. If anything, it’s a sign of just how low the Monsanto brand and reputation has plummeted, forcing it to try and improve its image by sidling up to Bayer, a participant in some of the cruelest crimes in human history.

While these types of mergers are nothing new to the agribusiness sector, where consolidation has been king for decades, last year’s proposed mega-mergers shattered the record for such deals. There were $125 billion worth of proposed agri-chemical mergers in 2016, nearly doubling the previous record of $65 billion in 2010. In addition to the proposed Bayer/Monsanto deal, there are also pending mergers between Dow and DuPont as well as Syngenta and the Chinese National Chemical Corporation.

This intense consolidation of the industrial agricultural sector, where only a few corporations control everything from seeds to fertilizers to pesticides, not to mention all the research and development that it also monopolizes, has been devastating to the U.S. farmer. Fewer choices for farmers has meant dramatically fewer farmers, squeezed out by the crushing duality of high-priced inputs and increasingly lower prices paid for farm goods, particularly commodities like dairy, corn, cotton, wheat and soybeans.

The Wall Street Journal recently published a sobering account of the pure economic calamities facing the American farmer, which now number less than 2 million, the lowest number since the 1800s. Its title didn’t beat around the bush: “The Next American Farm Bust is Upon Us.” The sad reality for farmers is that while billion-dollar mergers are taking place among their suppliers and buyers, on-farm income continues to plummet deeper into negative numbers. The USDA’s Economic Research Service predicted last year that on-farm income in the U.S. was projected to be around minus-$1,400 for 2017 (yes, that’s a negative number). But the Wall Street Journal points to figures closer to minus-$6,000, as news of even higher costs and lower farm-gate prices sink in.

The message is clear: If you want to farm, you better have a second (or third) job to make ends meet. Here’s how one Midwestern grain grower summarized his employment options to the Wall Street Journal: “Do I go work at Walmart as a greeter or as a parts man at the mechanics shop?”

It’s an economic reality far removed from the boardrooms contemplating billion-dollar mergers or the CEOs dining on gold plates at Trump Tower.

Bayer: A History of Shame

Corporate mergers and cartels have played a central role in Bayer’s history, beginning in 1904, when it joined with the other German giants BASF and AGFA, the largest chemical and film corporations in the world at the time, to form the first chemical cartel, often referred to as Baby Farben. Then, after Germany’s loss in the First World War, and under the leadership of Bayer’s Carl Duisberg, the nation’s entire chemical industry was merged to become IG Farben. It was instantly the world’s largest cartel at the time and the biggest corporation in Europe. IG Farben was also decidedly conservative and opposed the more liberal policies of the Weimar Republic. Instead, large donations from IG Farben corporations went to national conservative parties, and ultimately, to the Nazis.

At Bayer, and other IG Farben laboratories, research and development was carried out on numerous chemical war gases. The inventor of phosgene gas, Fritz Haber of BASF, successfully advocated for its use in World War I. Similarly, Bayer’s Duisberg was personally involved in the development of mustard gas and pushed successfully for its use in WWI, contrary to international law. Moreover, the inventor of sarin and tabun gasses, Gerhard Schrader, was the head of Bayer’s pesticides department after World War II. Sarin is the gas that was used in the 1995 Tokyo subway attack that killed 12 people, and more recently, against Syrian Sunni rebels, killing an estimated 1,200. And a subsidiary of IG Farben, BASF, supplied Zyklon B (the “final solution” cyanide gas) that was used in the Nazi gas chambers.

IG Farben was a central player in the conquests of the Third Reich. As countries were conquered, IG Farben followed the troops and took over considerable parts of the occupied nations’ chemical, coal and oil industries. The Bayer/IG Farben leadership had all joined the Nazi Party by 1937, playing leading roles in the orchestration of Nazi atrocities. In the war criminal trials in Nuremberg, the IG Farben cartel was also on trial.

“It is undisputed that criminal experiments were undertaken by SS physicians on concentration camp prisoners,” declares a passage from the Nuremberg findings. “These experiments served the express purpose of testing the products of IG Farben.”

These horrific experiments under Nazi directives were known about and approved by the highest echelons of IG Farben, as is documented by Joseph Borkin’s book, The Crime and Punishment of IG Farben. While many were convicted as war criminals in Nuremberg, none of the IG Farben executives served sentences longer than four years and all were able to continue their corporate careers. Fritz ter Meer, for example, convicted of plunder, spoliation, slavery and mass murder, became chairman of the Supervisory Board of Bayer in 1956 and held that position until 1964.

In one investigation by the U.S. Senate in 1945, and reported on by Borkin, the Bayer brass on trial asked for sentencing leniency based on the argument that the Auschwitz victims had “not been made to suffer particularly badly as they were to have been killed anyway by the Nazis, but also on the grounds that the experiments had a humanitarian aspect in that the lives of countless German workers were saved thereby.”

Following the Allied victory in the Second World War, Bayer was restricted in the production and marketing of its products in the U.S., France, England and other parts of Allied Europe. Moreover, U.S. regulators were attempting to seize Bayer’s chemical plants in the U.S. But in order to hide from its past and continue its corporate hegemony in the U.S., Bayer orchestrated a merger with Monsanto in 1954, giving rise to the Mobay Corporation. While Bayer may have been stripped of its coveted aspirin patent and other sales and marketing opportunities as a result of its Nazi collaboration, its newly reconstituted entity—Mobay—allowed them to remain an economic powerhouse in the U.S.

In 1964, however, the U.S. Justice Department had seen enough of the predatory practices of the Mobay Corporation. It filed an antitrust lawsuit against Moba y, and insisted that it be broken up. The suit argued that Mobay was seeking to discourage competition and that its economic concentration within the chemical industry was a clear and undeniable infringement of U.S. antitrust laws. In 1967, a federal judge ruled in the government’s favor and ordered Monsanto to sell all of its interest—50 percent—in Mobay back to Bayer.

y, and insisted that it be broken up. The suit argued that Mobay was seeking to discourage competition and that its economic concentration within the chemical industry was a clear and undeniable infringement of U.S. antitrust laws. In 1967, a federal judge ruled in the government’s favor and ordered Monsanto to sell all of its interest—50 percent—in Mobay back to Bayer.

While this effectively ended their corporate marriage, it didn’t impede their chemical romance.

In the years since the breakup, Bayer and Monsanto have unofficially rebounded and worked together to promote Agent Orange in Viet Nam. More recently, in a formidable one-two punch against Monarch butterflies, honeybees and bird populations, Monsanto supplied the Roundup and Bayer provided the neonicotinoids. And then, of course, there have also been human health consequences, water quality issues, and the economic strangulation of the American farmer as these two chemical titans waged their collective wars on bugs and nature.

While Bayer tries its best to put a soft-focus on its past, referencing its aspirin breakthrough of 1898, but forgetting about its heroin-based children’s cough syrup released about the same time, it is a history that should never be forgotten. It’s a sordid past made possible largely by the result of mergers and acquisitions, where corporate power became so great that it overwhelmed laws and simple human decency. At the very least, it cannot not be allowed to play the fair-haired child in its latest attempts to merge with the ethically challenged Monsanto.